Rating: ****

Tags: Computers, General, Lang:en

Summary

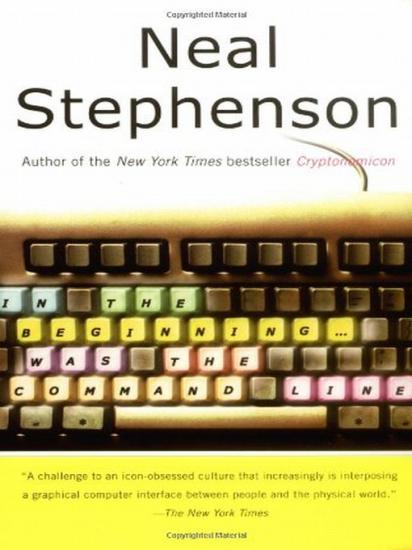

This is "the Word" -- one man's word, certainly -- about

the art (and artifice) of the state of our computer-centric

existence. And considering that the "one man" is Neal

Stephenson, "the hacker Hemingway" (

Newsweek) -- acclaimed novelist, pragmatist, seer,

nerd-friendly philosopher, and nationally bestselling author

of groundbreaking literary works (

Snow Crash, Cryptonomicon, etc., etc.) -- the word

is well worth hearing. Mostly well-reasoned examination and

partial rant, Stephenson's

In the Beginning... was the Command Line is a

thoughtful, irreverent, hilarious treatise on the

cyber-culture past and present; on operating system tyrannies

and downloaded popular revolutions; on the Internet, Disney

World, Big Bangs, not to mention the meaning of life

itself. ** Neal Stephenson, author of the sprawling and engaging

Cryptonomicon, has written a manifesto that could be

spoken by a character from that brilliant book. Primarily,

In the Beginning ... Was the Command Line discusses

the past and future of personal computer operating systems.

"It is the fate of manufactured goods to slowly and gently

depreciate as they get old," he writes, "but it is the fate

of operating systems to become free." While others in the

computer industry express similarly dogmatic statements,

Stephenson charms the reader into his way of thinking,

providing anecdotes and examples that turn the pages for

you. Stephenson is a techie, and he's writing for an audience

of coders and hackers in

Command Line. The idea for this essay began online,

when a shortened version of it was posted on

Slashdot.org. The book still holds some marks of an

e-mail flame gone awry, and some tangents should have been

edited to hone his formidable arguments. But unlike similar

writers who also discuss technical topics, he doesn't write

to exclude; readers who appreciate computing history (like

Dealers of Lightning or

Fire in the Valley) can easily step into this

book. Stephenson tackles many myths about industry giants in

this volume, specifically Apple and Microsoft. By now, every

newspaper reader has heard of Microsoft's overbearing

business practices, but Stephenson cuts to the heart of new

issues for the software giant with a finely sharpened steel

blade. Apple fares only a little better as Stephenson (a

former Mac user himself) highlights the early steps the

company took to prepare for a monopoly within the computer

market--and its surprise when this didn't materialize. Linux

culture gets a thorough--but fair--skewering, and the

strengths of BeOS are touted (although no operating system is

nearly close enough to perfection in Stephenson's eyes). As for the rest of us, who have gladly traded free will

and an intellectual understanding of computers for a

clutter-free, graphically pleasing interface, Stephenson has

thoughts to offer as well. He fully understands the limits

nonprogrammers feel in the face of technology (an example

being the "blinking 12" problem when your VCR resets itself).

Even so, within

Command Line he convincingly encourages us as a

society to examine the metaphors of

technology--simplifications that aren't really much

simpler--that we greedily accept.

--Jennifer Buckendorff

After reading this galvanizing essay, first intended as a

feature for Wired magazine but never published there, readers

are unlikely to look at their laptops in quite the same

mutely complacent way. Stephenson, author of the novel

Cryptonomicon, delivers a spirited commentary on the

aesthetics and cultural import of computer operating systems.

It's less an archeology of early machines than a critique of

what Stephenson feels is the inherent fuzziness of graphical

user interfacesAthe readily intuitable "windows," "desktops"

and "browsers" that we use to talk to our computers. Like

Disney's distortion of complicated historical events, our

operating systems, he argues, lull us into a reductive sense

of reality. Instead of the visual metaphors handed to us by

Apple and Microsoft, Stephenson advocates the purity of the

command line interface, somewhat akin to the DOS prompt from

which most people flee in a technophobic panic. Stephenson is

an advocate of Linux, the hacker-friendly operating system

distributed for free on the Internet, and of BeOS, a

less-hyped paradigm for the bits-and-bytes future. Unlike a

string of source code, this essay is

user-friendlyAoccasionally to a fault. Stephenson's own set

of extended metaphors can get a little hokey: Windows is a

station wagon, while Macs are sleek Euro-sedans. And Unix is

the Gilgamesh epic of the hacker subculture. Nonetheless, by

pointing out how computers define who we are, Stephenson

makes a strong case for elegance and intellectual freedom in

computing. (Nov.)

Amazon.com Review

From Publishers Weekly

Copyright 1999 Reed Business Information,

Inc.